History of the Transcontinental Railroad and US Mail

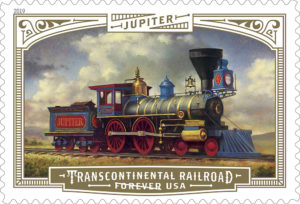

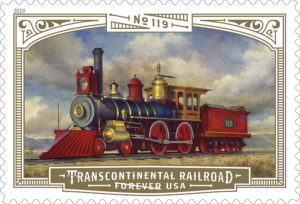

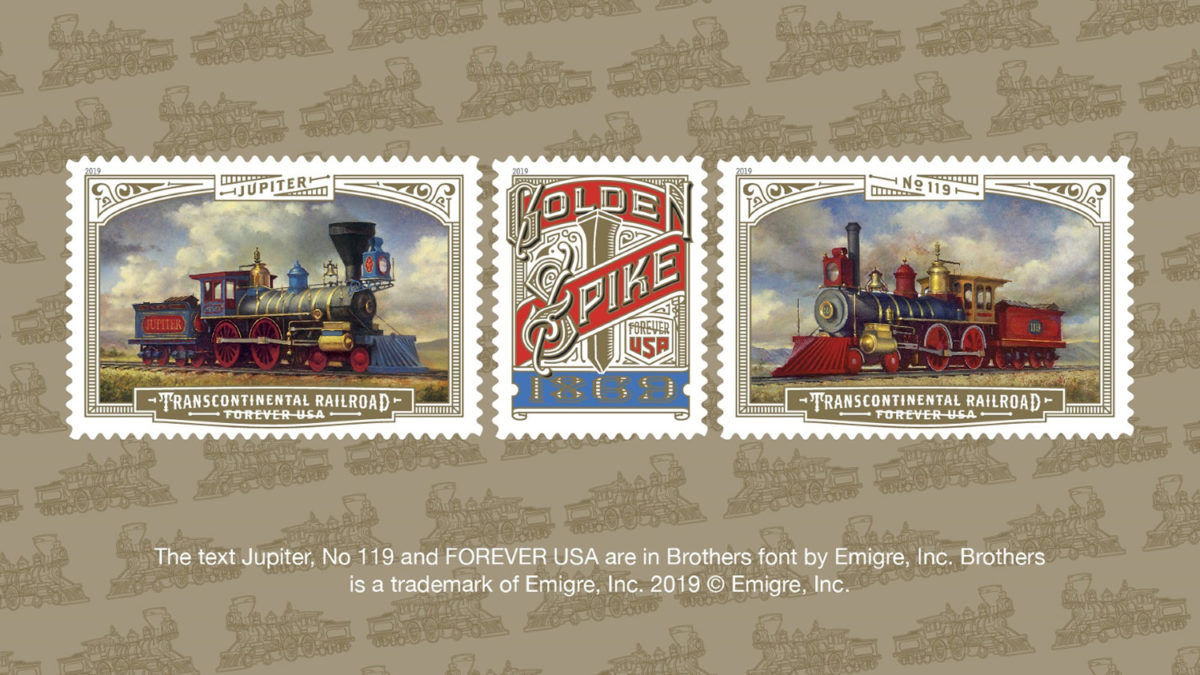

On May 10, 2019, the U.S. Postal Service will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad with a set of Forever stamps. Construction of this railroad during the 1860s was the wonder of the age. Its completion was marked by the “Golden Spike Ceremony,” held when rail lines built by the Central Pacific Railroad Company from the west and the Union Pacific Railroad Company from the east were joined at Promontory Summit, Utah.

With the completion of the transcontinental link, it was possible — for the first time — to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts on a nearly continuous rail line. Not only did the new railroad facilitate the transportation of people and goods, it also allowed the mail to travel with unprecedented speed and ease.

Moving the Mail

Before railroads, mail was transported on horseback, in wagons, or by boat. The Post Office Department recognized the value of railroads in moving the mail as early as 1832, when stagecoach contractors on a route from Philadelphia to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, were granted an allowance of $400 per year “for carrying the mail on the railroad as far as West Chester.”

In 1835 Postmaster General Amos Kendall predicted, “The multiplication of rail-roads will form a new era in the mail establishment. They must soon become the means by which the mails will be transported on most of the great lines of intercommunication.”

Congress saw the advantages of moving the mail by rail, too. In 1838, all railroads in the United States were declared to be post routes and the Postmaster General was instructed “to cause the mail to be transported thereon, provided it can be done upon reasonable terms.” By 1850, 6,886 miles of railway were used to carry the mail; by 1860 that mileage had quadrupled to 27,129. Most of that track, however, lay east of the Mississippi River.

When California entered the Union in 1850, it was distant and isolated from the East. Mail for the Pacific Coast had to travel many weeks — first by steamship to Panama, then overland across the isthmus, and finally by sea to San Francisco. Postmaster General Nathan Hall wrote, “The conveyance of correspondence … between the Atlantic and Pacific portions of the United States, has become a large and important branch of our mail service.” Yet he acknowledged that due to the great distance, “The mail service in California and Oregon … is still in an unsettled state.” Overland mail routes to California were established in the 1850s, but the routes were hazardous and service was erratic.

Between San Francisco and the nearest railroad lay nearly 2,000 miles of mountains, deserts, rivers and plains. The idea of connecting California to the rest of the nation by rail was but a distant dream. The technical challenges of scaling the Sierra Nevada Mountains were formidable, but not nearly as insurmountable as the political hurdles. Politicians from the North and the South were stalemated over which route the railroad should take. It wasn’t until after the southern states seceded in 1861 that the deadlock was broken.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, to provide for the “safe and speedy transportation of the mails, troops, munitions of war, and public stores.” The act created the Union Pacific Railroad Company and authorized it to build a railroad westward from Nebraska, to connect with a road to be built eastward by the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California. Construction began the following year, eastward from Sacramento, California, and westward from Omaha, Nebraska.

Over the next six years, construction progressed and the distance between the ends of the two railroads grew shorter. The Post Office Department contracted with Wells, Fargo & Co. “for the transportation of the United States mails between the western terminus of the Union Pacific railroad and the eastern terminus of the Central Pacific … until the two railroads should meet.”[1]

The two ends finally met on May 10, 1869, at a point 66 miles from Salt Lake City. The effect on speeding the mail was dramatic. Before the completion of the transcontinental railroad, mail averaged between 16 and 20 days to travel from the Missouri River to California. In October 1869, the average time from San Francisco to Washington, DC, was 7 days, 7 hours, and 11 minutes. The quickest trip that month, from San Francisco to Washington, DC, took just 6 days, 15 hours.

The stunning impact of the new railroad was summed up in a speech given by the San Francisco businessman, A.S. Gould, in September 1869: “The mind well-nigh loses its balance in the fact of this wondrous revolution, and yet it is true, the Pacific Railroad has emerged from the ideal to the real, and California … is brought nearer than ever to the necessities of the east and of the world.”[2]

Steve Kochersperger, Senior Research Analyst, Postal History, U.S. Postal Service

[1] Annual Report of the Postmaster General (1869).

[2] Daily Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) Sept. 28, 1869.